In the world of investment management there is an idea that blindfolded monkeys throwing darts at pages of sharelistings can select portfolios that will do just as well, if not better, than both the market and the average portfolio constructed by professional asset managers. If this is true, why might it be the case?

The dartboard

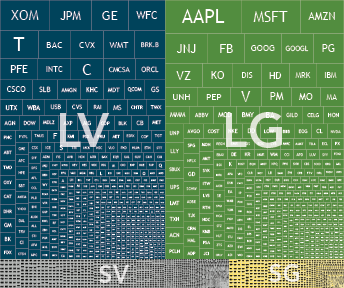

Example 1 shows the components of the Russell 3000 Index (a good proxy for the US stock market, the largest in the world) as of 31 December 2016. Each share in the index is represented by a box, and the size of each box represents the company’s market capitalisation. For example, Apple (AAPL) is the largest box since it has the largest market cap in the Russell 3000 index. The boxes get smaller as you move from the top to the bottom of the example, from larger companies to smaller companies.

The boxes are colour coded based on market cap and whether they represent value or growth shares. Value shares have lower relative prices (as measured by, for instance, the price-to-book ratio) and growth shares tend to have higher relative prices. In the example, blue represents large cap value shares (LV), green represents large cap growth shares (LG), grey is for small cap value shares (SV), and yellow is for small cap growth shares (SG).

Imagine therefore that Example 1, as a proxy for the overall US stock market, is similar to a portfolio that, in aggregate, professional asset managers hold in their competition with their simian challengers. This is because for every investor with an overweight holding in a company (relative to its market cap weighting), there must also be an investor underweight in that same company. Therefore, in aggregate, the average investment portfolio looks like the overall market.

Example 1. US stocks sized by market capitalization

For illustrative purposes only. Illustration includes constituents of the Russell 3000 Index as of 31 December 2016, on a market-cap weighted basis segmented into large value, large growth, small value, and small growth. Source: Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. Please see Appendix for additional information.

1. The ratio of a firm’s market value to its book value, where market value is computed as price times shares outstanding and book value is the value of shareholder’s equity as reported on a company’s balance sheet

2. For more on this concept, please see “The Arithmetic of Active Management” by William Sharpe at https://web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/active/active.htm

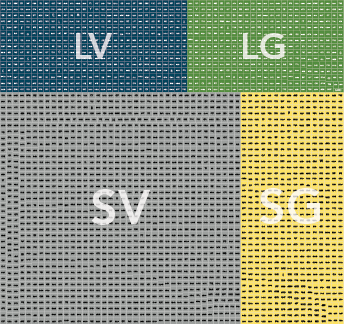

Example 2, on the other hand, represents the board the monkeys are using to play their game. The boxes represent the same companies shown in Example 1, but companies are weighted equally, not by market cap. For example, Apple’s box is the same size as every other company in the index, despite its much larger market cap. If monkeys were to throw darts at pages of stock listings, Example 2 is more representative of what their target would look like.

The significant differences between Examples 1 and 2 are clear. In Example 1, the surface area is dominated by large value and large growth (blue and green) companies. In Example 2, however, small cap value companies (in grey) dominate.

Why does this matter? Research has shown that, historically over time, small company shares have had excess returns relative to large company shares. Research has also shown that, historically over time, value (or low relative price) companies have had excess returns relative to growth (or high relative price) companies. Because Example 2 has a greater proportion of its surface area dedicated to small cap value companies, it is more likely that a portfolio of shares selected at random by throwing darts would end up being tilted towards companies that research has shown to have had higher returns when compared to the market.

Example 2. US stocks sized equally

For illustrative purposes only. Illustration includes the constituents of the Russell 3000 Index as of 31 December 2016 on an equal-weighted basis segmented into large value, large growth, small value, and small growth. Source: Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. Please see Appendix for additional information.

So should we all be throwing darts?

Probably not. This analysis does not mean that haphazardly selecting shares by the toss of a dart is an efficient or reliable way to invest. For one thing, it ignores the complexities that arise in competitive markets.

Consider the seemingly straightforward strategy of holding every company in the Russell 3000 Index at an equal weight (the equivalent of buying the whole dart board in Example 2). In order to maintain an equal weight in all 3,000 companies, an investor would have to rebalance frequently, buying shares of companies that had gone down in price and selling shares that had gone up. This is because as prices change, so will each individual holding’s respective weight in the portfolio. By not considering whether or not these frequent trades add value over and above the costs they generate, investors are opening themselves up to a potentially less than desirable outcome.

Instead, if there are well known relationships that explain differences in expected returns across shares, using a systematic and purposeful approach that takes into consideration real-world constraints is more likely to increase the likelihood of investment success. For example, such an approach would consider the drivers of returns and how to best design a portfolio to capture them, what makes for a sufficient level of diversification, how to appropriately rebalance and how to manage the costs associated with pursuing such a strategy.

The long game

What insights can investors glean from this analysis? First, by tilting a portfolio towards sources of higher expected returns, investors can potentially outperform the market without needing to outguess market prices. Second, implementation and patience are paramount. If you are going to pursue higher expected returns, it is important to do so in a cost-effective manner and to stay focused on the long term.

Finally, the importance of having an asset allocation suited to your objectives and risk tolerance, as well as remaining focused on the long term, cannot be over-emphasised. Even well-constructed portfolios pursuing higher expected returns will have periods of disappointing results. At Moore we can help you decide on a suitable asset allocation, stay the course during periods of disappointing results, and carefully weigh the considerations highlighted above.

Appendix

Large cap is defined as the top 90% of market cap (small cap is the bottom 10%), while value is defined as the 50% of market cap of the lowest relative price shares (growth is the 50% of market cap of the highest relative price shares.